Description

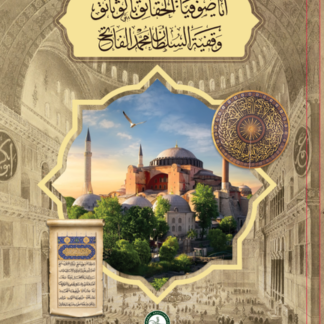

CONQUEST OF ISTANBUL AND CONVERTING THE HAGIA SOPHIA TO MOSQUE

MANY PAPERS WHICH HAVE BEEN PUBLISHED BY SOME HISTORIANS WERE NOT BASED ON ARCHIVAL DOCUMENTS ABOUT CONQUEST OF ISTANBUL AND HAGIA SOPHIA

On the allegations that Sulṭān Meḥmed the Conqueror took Constantinople by the might of the sword, he – especially with his conversion of the Church of St. Sophia into a mosque – razed the Christians’ places of worship, massacred the Byzantines, and, most importantly, devastated the city.

We should first state that even those Byzantine historians who witnessed the conquest in person did not dare utter such claims. Sulṭān Meḥmed the Conqueror’s fulfilment of the conquest of Istanbul as well as other places was within the decrees of the Islamic law in its entirety. According to Islamic law, even during actual fighting Islamic troops are forbidden to carry out some acts against the persons and goods of the enemy. One of the most significant reasons that enabled our ancestors to leap from one victory to another is that they adhered to these principles verbatim ac litteratim. In fact, their triumphs were proportionate to their adherence to these essentials. (Upham, History of the Ottoman Empire, vol. I, pp. 196ff.; Colin Imber, Keiko Kiyotaki and Rhoads Murphey, Frontiers of Ottoman Studies: State, Province, and the West(Edinburg: I.B. Tauris, 2005), pp. 213ff.)

Let us now summarise the prohibited acts: killing enemy soldiers through tyranny and torture, murdering people like women, children, or slaves who had come to the battlefield to serve their masters, the disabled, and the chronically ill, the elderly, the sick, the mentally sick, etc. who did not fall into the category of soldiers, and the ecclesiastics who lived in seclusion (nevertheless, if any one of these takes part in a war either physically, intellectually, or with his goods they may then be killed), mutilating the organs (muthlah) of people and animals, acting contrary to a promise or treaty, burning crops, forests, and trees (unless strategically required), committing adultery or any illicit relations, killing hostages, cutting off the head or any organs of the dead, or committing a massacre, and killing close relatives, especially the father, or anybody who is not involved in war like tradesmen and merchants. Although there are also some other prohibitions, we suffice with the aforementioned ones.

The above-mentioned decrees are quoted from the book by Molla Ḥusrev, the Conqueror’s Qāḍīʻaskar. Therefore it would only be a malignant example of uttering words without any proof to ascribe such acts to a state official who accepted and applied the said decrees as his official law codes. (Molla Ḥusrev, Durar wa Ghurar, vol. I, pp. 282ff.; Mevkufati, Translation of Multekā, vol. I, p. 343; Damad, Majmaʻ al-Enhur Sarh-i Multeka al-Ebhur, vol. I, pp. 643ff.)

With respect to how Istanbul was conquered and the St. Sophia event, we should note the following.

According to the provisions of the law of Islamic states, places of worship pertaining to Ahl al-Kitāb (“People of the Book”) in such states where conquest through peaceful means have taken place are never harmed. However, the construction of new ones is not allowed while those already existing may be restored. But in countries captured through wars the situation is just the reverse. That is, the Muslim ruler – if he so wishes – may destroy all the temples pertaining to other religions and deport non-Muslims. Istanbul was conquered through war. The legal rationale for the conversion of St. Sophia and similar churches into mosques was that very provision. As a matter of fact, if that provision had been applied throughout Istanbul, all the churches and synagogues in Istanbul would have been destroyed. After Sulṭān Meḥmed the Conqueror – who had conquered Istanbul through the divine aid of Allah and the might of his sword – had transformed HAGIA SOPHIA into a mosque, he received a delegation of priests and rabbis, who told the Sulṭān that he had conquered Istanbul and therefore he might – if he so wished – leave no churches or synagogues there as a right that had been granted to him by international law. Nonetheless, they insistingly requested him to treat their communities and worship places as if he had conquered the city peacefully.

Sulṭān Meḥmed the Conqueror, in consultation with the Islamic scholars in his entourage, did not reject their demand and no more were converted into mosques. As a result, he did not touch churches and synagogues although he had right to do so. In this regard, Abussuʻūd Efendi, a renowned Şeyḫulislam of the Ottoman state, explained that those churches and synagogues that have existed exiting up to today reflected the Conqueror’s notion of freedom for religion and conscience. The original text of that fatwā (judgment) is as follows:

Question: Did Sulṭān Meḥmed Han conquer Istanbul and the neighbouring villages by force?

Answer: What is known to us is that it was conquered by force. Nevertheless, the ancient churches point to a peaceful conquest. This issue was investigated by the state in 945. Two very important witnesses were found, one of whom was 130 years old and the other 110. They testified that the Jewish and Christian communities concluded a secret agreement with Sulṭān Meḥmed the Conquerer that they did not help the tekfur and the Sulṭān did not take them as slaves (seby etmeyüb) and allow them to live in Istanbul. Thus old churches remained as they were previously. Abussuʻūd has written this fatwā. (Molla Ḥusrev, Durar wa Ghurar, vol. I, pp. 282ff.; Mevkufati, Translation of Multekā, vol. I, p. 343; Damad, Majmaʻ al-Enhur Sarh-i Multeka al-Ebhur, vol. I, pp. 643ff.).

What we have reported here is affirmed by historians. Sulṭān Meḥmed the Conqueror sent Damad Kasim Bey the Isfandiyarid, on 23 May as an envoy to the Byzantine Empire to convey the following information. The city would fall at the first general attack, and the fact must have been admitted by the Emperor himself, who was a perfect soldier. If they surrendered peacefully, no harm would by any means be done to their lives or goods as per the decrees of Islamic law. However, if it was captured by force, blood would be shed, and no guarantee would be given. Unfortunately when the Emperor rejected the peaceful means despite the proposal, the city was conquered by force. All the same, the Conqueror treated the Byzantine Emperor in the aforementioned way. As a matter of fact, the fact that Meḥmed the Conqueror did not totally destroy the mosaics of St. Sophia and did not tear down the city walls of Istanbul openly reflects the Conqueror’s attitude on this subject.

As can be seen, the promise of Sulṭān Meḥmed the Conqueror was that “he would allow the Christians to erect a church next to each church in Serbia” was actually effectuated in Istanbul. For instance, does the existence of the Patriarchate of the Anatolian Greeks and the adjacent church next to a mosque in Abdi Subaşı quarter in Fener, Istanbul, not reflect the real freedom of religion and conscience in the Ottoman state? Is the permission for the Anatolian Greeks to build a church precisely opposite the Mihrimah Sulṭān Mosque at the end of Edirnekapi Street not tangible evidence of the same freedom?

On the other hand, the allegation that Istanbul was devastated is not correct. Rather than replying to this question in detail, we will quote a report from mass media like CNN, Time, and the like, which ranked the conquest of Istanbul among the most significant hundred events of the last millennium:

While Istanbul had been thoroughly a dead city in ruins before it was conquered by the Conqueror, it turned out to be the commercial centre of both Europe and Muslim countries and a prosperous world city after the conquest. Yet on the other hand, even Ouspensky, a Russian historian, dared to say: “The Turks acted much more humanely and tolerantly in 1453 than the Crusaders did in 1204.

(Ibn al-Kamal, Tawārīḫ-i Āl-i Osman, Book VII, pp. 62ff.; Baştav, Şerif, “XIV. Asırda yazılmış Grekçe Anonim Osmanlı Tariḫine göre İstanbul’un Muhasarası ve Zabtı,” pp. 51-82; Ālī, Kunh al-Aḫbār, vol. V, pp. 251-60; Solakzāde, Tariḫ, pp. 191-201; Aşikpaşa-zāde, Tariḫ, pp. 141-43; Clot, Fātiḥ, pp. 60ff.; for opposing views see Aydın, Fātih ve Fetih, Mitler ve Gerçekler, pp. 66-67, 94-95, 127-28; P.D. Ouspensky, In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1949).)